This piece was originally published in 2018. As of 2023 Canada and several states in the US have passed laws permitting “medical assistance” with dying. I highly recommend reading THIS about the slippery slope this presents in our current healthcare climate.

I took my shoes off upon entering the den of death, I guess out of respect. He was 83, born in 1932, married in 1954 and dead in 2015. He smoked his last cigar deliberately, had his last meal quickly and took on death joyfully they said. Alzheimer’s is a twisted dimension in which everything warps until the most opposing concepts blend and meld into some kind of personal mythology, existing within its own unit of time. A time not so neatly stored between now and then. A blurry film of confusion wrapped around the mundane. It takes the mind for a sick ride until it takes the mind completely.

He knew he had it very early on. He went for a single test, to confirm, and then moved forward with his plan while hating every bit of the diagnosis. Though he wasn’t necessarily image concerned, his intellect, or the perception of his intellect, was held in his highest regard. The brain was everything to him - it created the sensation of living and would be extinguished completely in death. He never concerned himself with the frilly edges of an afterlife, the concept just didn’t check out. Through delta waves, information could be organized and the man could be curated. From a starved childhood a wealth of wisdom could grow. Sapience by way of sawdust. He pushed the limits of his disease and continued studying until the end. Hosting lectures at the senior center on the dangers of billionaires and the merit of Twain even in the last month of his life. Upon death he had 500 or so books crammed into his awkward one bedroom apartment. He always had a strong hunger for the truth, almost as if it were a fixed point, artfully hidden just out of view.

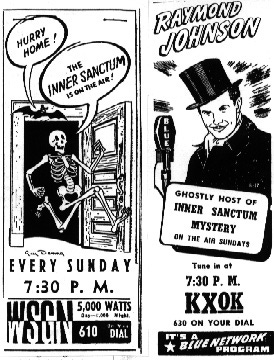

When I was a child he would tell me stories about living on the North side of town. It was around 1940, and a radio show by the name “Inner Sanctum” would air in the evenings. The mildly morbid holds an impossible interest for most children, even in the face of their initial fear. He told a story of being home alone one night, as he often was, and listening in to the show. Stomach fluttering with a ghostly giddiness. That particular episode was so frightening that he was thrust into a terrified, anxious state. It was an existential fear that pushed him to run out of the small house and sprint down the street. He said he did it to know he was still alive - that the world was still there. He told me the images of horror rose up in him and echoed every doomed thing he had ever heard about hell, coalescing into a roar he was sure would kill him and send him straight to the fiery gates. He made it to the streetlamp and caught his breath until the fear subsided enough that he could return to the empty house. This experience was often cited as a contributing factor to the atheism of his adulthood. We know when God has stopped listening.

Again, in old age he was petrified by the thought of becoming a “vegetable”. It was during this period that I became his daily caretaker. Our tiny, fractured family made a point to gather around him when we could manage. Mom had to fly in from across the country, my uncle struggled with addiction and punctuality, but we tried. On one of these fragile family outings he announced that he was going to die on his own timeline. Enough with the bullshit. Man was all there was. Man was God and God has a master plan. He asked for help procuring a gun. His first proposal was grim: rent a room, wrap a towel around the faulty, infected head, pull the trigger and leave a tip for the poor soul that found him. To understand what would make a person desire that demise so openly, you have to empathize with the condition. His own inner sanctum was becoming a frightful place. First it was faces, names and dates, but we had simple solutions to these slips. I was there with the schedule, with the prepared lunch and with a tug on the sleeve. The disease multiplied and complicated. All things wrinkling in dementia’s distortion. The room changed shape around him, deceased friends paid visits and the furniture was stolen. The streets of the town he was born in became fuzzy. His affection turned to madness and with an acid tongue he served me lashings.

Derek Humphrey’s book Final Exit, suggests suicide by helium inhalation. Have you ever bought the instrument of death for a loved one from a Party City? -1000/10, do not recommend this incredibly disturbing and surreal life experience!

Some time before the dimensions of his mind stretched towards derangement, he devised a more humane proposition for D-Day. I was hurt deeply by this. I believe mom was devastated too, but we remained on our mother/daughter intimacy diet as usual. Through this bizarre era we could only support a man as sternly autonomous as him. He wasn’t going to be a victim of nature’s lackadaisical timing. This geriatric purgatory was a surreal space to exist in as a newly-minted 20 year old. I had spent my whole life avoiding and fearing death and then suddenly we were planning for it as a desirable alternative to what life was surely serving. There was much to be done every day. Who knew there were so many loose strings to tie up before one dies? We wrote his obituary together and were both pleased with how it came out. He wanted me to include a specific quote about not fearing the end, about standing up in the calm wind of understanding. It was something I meditated on often. Still do… What did he understand that the rest of us don’t?

In between D-Day planning there was still life. When tidying up or making lunch, I would put on music for us to both enjoy. I’ve since heard this is a positive therapy for those suffering with Alzheimer’s. We listened to Patsy Cline most of the time. He would perch on the bed with his slacks on and fall backwards into his previous life. It was in these quiet moments I felt the closest to grasping his predicament. The music cracked out of the cheap speakers and grounded us both in the Now. He would fall asleep and I would fall to pieces.

After his death I was in shock, frozen in a lack of feeling. It took a long time to believe it had happened at all because nothing felt that different. There was no body, no blood, no scrambling to plan. Just a mark on the carpet where the medical examiner’s stretcher had rolled. We didn’t speak about it with anyone because of the circumstances. There was a fear of being arrested, persecuted somehow for allowing him to choose his destiny. In this moral hellscape, even death with dignity is a crime. The nurses who helped him on the way out flew down from Chicago and back again without saying much at all other than he was happy to leave. They said he smiled as he passed. Almost immediately my mother and I left for a trip abroad together. Iceland. A land of dramatic negatives was fitting. The bleakness and black beaches seemed to mirror some kind of shared trauma between us. Empty hearts turned inside out to a landscape. Craggy rocks with no trace of life. We were alone - together on an orphan island.

After he left I had so many questions. Did it hurt? Did you mean the nasty things you said? What should I do with you and Grandma’s things? It felt sacrilegious to throw them out. Their artifacts of love and human life would lose all meaning without a witness. An already small voice would be lost in the primordial din. It still didn’t seem real even as the weeks passed. He was here, in a body, with his old hand tucked in my young hand, then he was a heavy steel box of ashes. I still have dreams I find him in the woods, in a canyon, in a cabinet and he is full of color and life and this has been a joke. There must be a misfire somewhere in my object permanence module. I drive downtown every day on the way to work and I pass by the building he sold gum to businessmen in as a child. I pound the pavement too, scared of hell, of dying alone, of losing myself, trying to catch my breath and quiet the roar. I kept the books, I kept the furniture, I kept the ashes I kept the strange, silent sorrow of a life lost. If I don’t keep it who will?